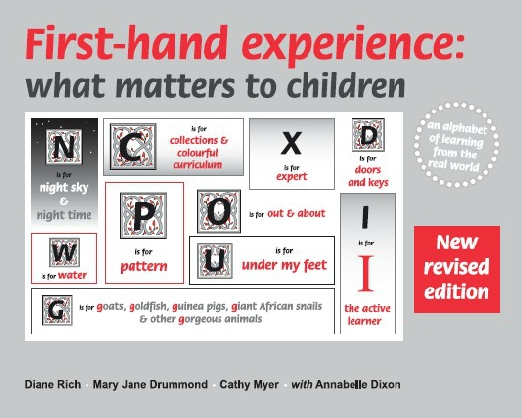

First-hand experience: what matters to children (2014)

First-hand experience: what matters to children (2014)

An alphabet of learning from the real world

by Diane Rich, Mary Jane Drummond, Cathy Myer with Annabelle Dixon

| Authors The authors are experienced and respected education consultants. They have come together to work on a variety of projects for many years, and have always been committed to promoting what matters to children. Diane Rich has been involved in children’s learning for many years, as play worker, teacher, advisory teacher, researcher, consultant, author, trustee for children’s charities. She co-ordinated the work of the What Matters to Children team from 2005-2013. Diane recently worked as a visiting lecturer at the University of Roehampton. She continues to work as a freelance consultant and runs Rich Learning Opportunities: keeping creativity, play and first-hand experience at the heart of children’s learning. Mary Jane Drummond is a writer and researcher with an abiding interest in young children’s learning. Before retiring she worked for many years at the University of Cambridge, Faculty of Education. Cathy Myer has been a teacher, advisory teacher, university lecturer and freelance education consultant. Although now retired, Cathy remains passionate about children and their capacity to learn from their experiences of the real world. Annabelle Dixon (1940-2005) Annabelle’s classroom was, in the words of a friend, ‘a place of genuine intellectual search.’ As psychologist and teacher she is committed to offering first hand experiences to children as the essential basis for such a search. Denise Casanova and Andrea Durrant were co-authors of the 2005 edition of First hand experience: what matters to children. |

| BOOK DEDICATION The authors dedicate the 2005 and 2014 editions of ‘First-hand experience: what matters to children’ to our dear friend and colleague Annabelle Dixon (1940-2005) in memory of her work with children and adult educators |

What is this book?

This new revised 2014 edition is for all teachers, and other educators of children from birth to 11, who seek to provide a curriculum, built on real, worthwhile experiences. It aims to support educators in thinking more deeply about children’s active learning, stimulated by high quality first-hand experiences. Each page has been developed as a springboard from which young and primary aged children, teachers and other educators can launch themselves into the mysterious and physical world in which we all live. With foreword by Sir Tim Smit.

Part one

• outlines the structure of the book

• explores the authors’ analysis of what matters to children

• examines the theoretical underpinnings of the work on which it is based

• describes how to use the book.

Part two has pages of different kinds:

• alphabet pages- which include the key elements: what matters to children, verbs and nouns as metaphors for children’s learning, big ideas, questions worth asking and books for children an adults

• learning stories- offered by educators who are committed to promoting first-hand experience with children

• alternative alphabet pages- which explore: active learning, important kinds of knowledge, the characteristics of worthwhile looking and listening, the characteristics of questions that stimulate children’s enquiries, important kinds of thinking that are stimulated by first-hand experience, and children as experts on the subject of their own learning.

• The book ends with an outline of the principles that are the basis of the authors’ work and gives warm encouragement for educators to build on their experiences of using the book to continue to act as critically aware, observant, reflective and inventive supporters of children’s learning offering them countless first-hand experiences to feed their insatiable appetite for the world.

| CONTENTS Acknowledgements About the authors Foreword by Sir Tim Smit PART ONE Introduction to the revised edition The structure of the book C, I, K, L, Q, T, X, Z: these pages are different Encouraging voices old and new: theoretical underpinnings of our work How to use this book Focus on learning: bags and brushes Why an alphabet? E is for everything! What is a first-hand experience? PART TWO An alphabet of learning from the real world A is for alphabets A is for apple B is for bags B is for brushes C is for collections C is for colourful curriculum D is for doors (with K is for keys) E is for enemies F is for furniture G is for goats, guinea pigs, gerbils, giant African snails, goldfish and other gorgeous animals H is for homes I is for ‘I’the active learner J is for joining K is for knowing L is for listening and looking M is for mixing N is for night time N is for night sky O is for out and about P is for pattern Q is for questions R is for rain S is for surfaces T is for thinking U is for under my feet V is for variety W is for water X the expert Y is for yesterday Z is for zigzag …finding your way through the book Over to you References Index |

National book reviews

Nursery World, 25 (January 2007)

ReFocus Journal (Summer 2006)

Early Years Educator (January 2006)

Nursery Education (November 2005)

Vivian Gussin Paley (July 2005)

Times Educational Supplement, Book of the Week (June 24 2005)

First-hand experience: what matters to children

Our recommended choice…

First-hand experience: what matters to children

By Rich, D. Casanova, D. Dixon, A. Drummond, MJ. Durrant, A. Myer, C.

Reviewed by Wendy Scott, early years consultant

This thought-provoking book is described as an alphabet of real experiences. It offers a springboard rather than a prescription, designed to stimulate imagination as much as reflection. It would help parents as much as practitioners to understand the importance of direct experience for young children.

The A-Z headings cover a range of interconnected ideas, and it is easy to ‘zig-zag’ through them according to individual interests or priorities. For example, ‘I’ stands for ‘I’ the active learner at the centre, arguably including adults as much as children.

Learning stories link practice and principle through personal example of how adults have developed and expressed their educational philosophy through paying close attention to what matters to individual children. Insights gained through careful observation enable them to support, encourage and extend rather than direct or determine children’s enquiries. Sustained shared thinking from genuine questions demonstrably leads to higher achievement.

The authors quote Susan Isaacs’ view that children grow through their own efforts and real experiences, and show how and why this matters. They address complex issues with admirable directedness, simplicity and examples. Key points are supported by reference to earlier guidance as well as recent research, and include relevant reading for children too.

First-hand experience: what matters to children

ReFocus Journal

Issue three Summer 2006

Refocus is the UK network of early childhood educators, artists and others influenced in their practice by the preschools of Reggio Emilia.

I was attracted by the title

of this book which puts the child’s experiences firmly at the centre of their learning but was wary of the alphabetic framework used to present the real learning experiences recommended. Would there be a risk that they would become contrived to fit the model? I’m happy to say that the authors, all experienced educators, have not fallen into that trap. Instead the reader is taken on an exciting journey of reflective thinking using innovative approaches and suggesting several potential connections – all with many different possible pathways. They cover the many things, whether ideas or experiences, which help children to make sense of their world. The book resonates strongly with the philosophy of the pre schools of Reggio Emilia in which both child and educator are considered as co-researchers. Thinking and learning are ‘made visible’ through observation and listening and much, much more. For those educators who want to be part of a learning journey with children, this is your guide.

Each letter of the alphabet has its own section and I particularly liked the ‘Q is for questions’ section which gives the basis for all learning. My own trawl of finding any comprehensive literature on this subject had previously produced poor results. Here, guidance is given on adults questioning children as well as value to children’s own questions – even those awkward ones. Annabelle Dixon’s suggestions about keeping a question book are exciting and her comment, ‘There must be something for children to ask questions about. If there aren’t any things there won’t be any questions!’ says it all. The section, ‘E is for enemies’ offers us the basis for another investigative project. Questions such as ‘What makes an enemy?’ and ‘Do enemies have friends?’, with examples of children’s learning stories as starting points, are well worth reading to help access this complex subject.

Guidance on the best use of ‘First Hand Experience’ is clearly stated and all sections are well supported by lists of comprehensive references to stories, books and music in addition to the questions, connections and ideas. It is possible to use this book for dipping into for one-off practical (but not quick fix) ideas, which in turn can grow and develop into new pathways. Or for those inspired by the values and philosophy of Reggio Emilia, it can be used for longer, reflective projects to explore abstract concepts and experiences. The back cover describes the book as ‘a springboard from which children and educators can launch themselves into the mysterious and physical world in which we all live.’ I would thoroughly recommend it to all educators who want to do just that.

Solveig Morris is an independent consultant and ReFocus board member.

First-hand experience: what matters to children

A rich learning experience

Review by Jessica Waterhouse

Early Years Educator brings you another batch of the latest products and books on offer in the early years New Year marketplace

EYE Volume 7 No.9 January 2006

As we early years educators continue to advocate play against the formal, top down pressures of key stage 1, it is a breath of fresh air to come across a book like First-hand experience: what matters to children.

If you would like a boost of inspiration and nourishment for the soul from a book which asserts that children’s learning must come from their interests and that it is our jobs to facilitate this - then I wholeheartedly recommend this book!

The book sets out to help improve children’s opportunities to experience the world at first hand. Children are referred to as active learners. A motivating foreword from Tim Smit, chief executive of the Eden Project, introduces the mantra of ‘observation’ and states that observation is ‘both the foundation of all good science and also the basis for learning from your experience.’

The introduction also sets out the theoretical underpinning for the book and acts as a reminder of those who have gone before, both here and in other countries, such as the early years educators in Reggio Emilia, Italy.

These theories are related to the Curriculum Guidance for the Foundation Stage, which recommends that children should be offered experiences ‘mostly based on real life situations’. Within the book, first hand experiences are described as ‘handling and using authentic things, going to places and meeting people, and being out and about.’

The book is laid out in an alphabetic format. Starting from each given letter are lists, statements and thought provoking quotes relating to ’what matters to children, questions worth asking, big ideas, books and stories, things to do and investigate'.

The book suggests so many fabulous starting points - r for rain, w for windows, n for nothing, and y for yesterday. My favourite – b for bags – includes suggestions, such as precious bags (a doctor’s bag, a princess’s bag, money bags, a wallet) visits to a Royal Mail sorting office, a sleeping bag factory, a handbag shop – and key questions such as: ‘What makes a bag a bag?’ ‘What would a witch’s bag look like?’

The section includes great ‘making ideas’, such as making a sleeping bag for teddy, or making a bag for an umbrella.

The book creates excitement through being innovative and unusual. It does not have lesson plans (hooray!) and there is not a learning objective in sight.

It does have learning stories, which are accounts of how educators have helped children to learn from a first hand experience. Each starting point gives such a wealth of ideas across every area of the curriculum. Treat your early years team with this book!

First-hand experience: what matters to children

Nursery Education November 2005

Professional bookshelf…

First hand experience

First hand experience: what matters to children

sets out to reinstate real-world experiences at the centre of children’s learning. It takes the form of an A-Z exploration of real experiences, with the aim of helping young children to blossom into balanced, creative adults. Written by a team of experienced education researchers and consultants, this thought-provoking book offers an array of topics under each letter of the alphabet. The elements on each page include: what matters to children; things to do and investigate; big ideas; questions worth asking; suggested books and stories.

First-hand experience: what matters to children

Vivian Gussin Paley

Author, and former kindergarten and nursery school teacher, primarily at the University of Chicago Laboratory Schools. Winner of many awards including the MacArthur Award and John Dewey Society ‘s Outstanding Achievement Award.

Written shortly after the July 7 2005 bombings in London

‘Reading your new work, as filled with the optimism that goes along with a love of young children and what they are really like, it seems we are in a different world than the one depicted in the newspaper and on TV. But it is our job to concentrate on children and your 'First-hand experience ’ presents a fine and novel approach to the subject that will certainly capture the attention of educators, parents, and of all, people who enjoy being with children and are eager to explore new directions and old certainties.

I applaud you and your colleagues for daring to stop, look around, and begin at the beginning. Exactly what the children like to do. Your curiosity will lift all of us to a higher place from which to carry on our own observations.

First-hand experience: what matters to children

Times Educational Supplement 24.05.05

Sanity amid the madness

In a world distracted by targets and testing, Sue Palmer urges primary teachers to renew their faith in real and direct interaction with children.

First-hand experience: what matters to children

an alphabet of learning from the real world.

by Diane Rich, Denise Casanova, Annabelle Dixon, Mary Jane Drummond, Andrea Durrant and Cathy Myer.

Rich Learning Opportunities £25

"Read this book," writes Tim Smit in the foreword. "It may save lives."

When the creator of the Eden Project is that impressed by an educational tome, it must be worth a look, despite the rather chunky title.

Well, after a very good look, I’ll go further than Mr Smit. If you work in nursery or primary education, buy this book, read it, enjoy it and consult it daily until you’ve regained your professional identity. It’s aimed at those working with children aged between three and eight, but there are important issues for teachers of older children too. In a world where tests, targets and curricular objectives have driven us all into a sort of collective madness, it will at the very least remind you why you came into the job in the first place, And if enough of us rally to the cause it represents, it will save lives.

The authors, established authorities on early childhood education, remind us of the elemental importance for young children of real experiences and genuine human interaction. For children whose lives out of school are often spent largely in front of screens, this essential stage in development is too often neglected. When they come to school, our cock-eyed educational system forces us to rush them straight into the manipulation of symbolic information (reading, writing and numbers). God knows what long-term damage has already been done by this clash between contemporary culture outside school and our premature start to formal learning, but for the sake of coming generations we must redress the educational balance. This book is a wonderful starting point.

There’s an excellent introduction, explaining the theories that underpin the approach (theory which is almost daily being affirmed by neuroscientific research). I particularly liked the definition of the role of the educator ‘to provide the curricular food that will nourish and strengthen children’s powers… to organise children’s enquiries and experiences so that they are actively and emotionally engaged… and to value the learning that comes from these activities, using it to plan children’s next steps.’

I’m sure the many thousands of teachers I meet every year would agree this approach fits the needs of young children much better than the pursuit of fixed objectives, an over- academicised curriculum and an inflexible testing regime, which at present creates not only educational failure but countless behavioural problems. It’s certainly the message from the Effective Provision of Preschool Education project, which has found that ‘sustained shared thinking’ between children and informed early years practitioners is the most significant contributor to later educational success.

The main body of the book is an alphabet of powerful starting points for practice, from A is for Apples (grow them, cook them, eat them, investigate them, look at them in art, consider the "big ideas" they trigger; inner and outer; parts and wholes; classification; naming; growth; transformation and so on) to Z is for Zigzag, which sums up the book’s holistic – but nevertheless highly structured- approach to early learning. It all looks enormous fun. The alphabet pages are interspersed with "learning stories" – case studies by practitioners who have trialled the ideas with children – and the pleasure of reading them is considerably enhanced by their design; inspired use of colour, typeface and layout, creating instant accessibility.

Altogether a remarkable achievement and I can’t recommend First Hand Experience enough. However I do have one serious quibble. Nowhere does the book tackle the vexed question of how, alongside this child –centred approach, we deal with the teaching of literacy skills. There are many recommendations for good children’s picture books to share alongside investigations, but the teaching profession knows from bitter experience in the 1980s and 90s that literacy skills do not emerge from children’s joyous immersion in books and stories; they have to be carefully taught. In a TV –dominated culture where many children are no longer tuned into language through nursery rhymes and songs, the need for specific teaching of phonological and phonemic awareness is increasingly necessary. And without structured help in developing the physical skills that underpin handwriting, then refining the ability to get letters and words down on paper, many children (especially boys) are seriously disadvantaged.

Personally, I see no conflict between the authors’ holitic, interactive, child-centred approach to learning in general, and a systematic, teacher directed but child –friendly approach to the development of the skills required for reading and writing. The two approaches can run in parallel, as early years practitioners are well used to such balancing acts. There’s no reason to inflict a damaging testing regime on the under-eights, as is demonstrated in successful European countries such as Sweden, Finland and Switzerland, where the foundation of literacy skills are carefully laid during the early years. When formal literacy teaching begins in these countries ( at seven years old) the vast majority of children learn to read and write easily and painlessly by the time they’re eight.

This splendid alphabet of first-hand experience is essential if children are to grow into balanced, creative adults, but our pupils also need to learn how to use the alphabet themselves to decode and encode information symbolically. Literacy skills must be taught carefully and systematically during the first eight years. The fact that the book makes no reference to this leaves it open to attack or – even worse – to contemptuous dismissal by the powerful people who have locked us into our current, dangerously unbalanced, system.

A serious quibble then, but it doesn’t dampen my enthusiasm. I believe early years teachers are perfectly capable of sorting out the balancing act themselves, and all primary teachers are now ready for a more creative approach to their craft. Teachers just need the courage of their convictions and the justification to get on with it. So please buy this book: it can change your professional life.

Sue Palmer is an independent literacy consultant and co-author of The Foundations of Literacy (Network Press)